Hi all, Long time since the last update because of grad school, but I should be back with semi-regular updates in late June after I return from an Archeological site in Greece. Until then, I’ve created a few videos that should be released weekly. It expands on the idea of Antarctolestes surviving and will include several small ornithopods surviving the K-Pg. I am also thinking of doing a stand-alone video that would be completely separate from everything that would focus on the survival of a small Tapajarid and explore how they might evolve and the knock-on effects the survival of a pterosaur might have on the birds and mammals they compete against. The first video focuses on Antarctolestes and addresses the question of “Why didn’t the birds evolve into giant megatherapods.

Twelve years have passed since the world ended. For the first two years after the impact, the dust-induced photosynthetic shut-down devastated the planet's plant population, and for a further 10 years, that same fine silicate dust shot into the upper atmosphere reduced the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface by 10 to 20%. Most of the megafaunal dinosaurs that weren’t killed by the impact or the firestorms that spread across the globe in the first few days died within months of the catastrophe with the stragglers not surviving the decade-long Impact Winter that followed. Outside of a few crocodilians and turtles, no animals larger than 25 kilos survived. The age of the Dinosaurs had come to an end… but what if it hadn’t?

Along the shores of a small lake in the Tasmanian Gateway a strange bird shrieks and squawks near the remains of a long-dead Antarctic megaraptoran. An endling, hatched mere months after the impact, the apex predator of Antarctica grew up in a sick and dying world. The last of its siblings to survive, the enfeebled predator finally succumbed to starvation along the shore of the lake. The little shorebird near it is just a year old, but the lives of its parents were just as tough as that of the megaraptoran. Their genus, once spread across most of southern Gondwana, is now reduced to just a few pockets in Eastern Antarctica and Southern Australia.

The little male is lekking, eager to let any females in the area know that he is fit, and has secured a nice burrow, not far from the shoreline, for her to roost in during the winter. As he struts, waiting for a reply, he can hear the occasional cries of competing males, but they are few and far between. Surviving the end of the catastrophe may still mean the death of his dynasty if he and his competitors never find companionship. But our little male does not falter, even as the day drags on to mid-afternoon, he calls out to the fern forest eagerly waiting for a reply.

And then he sees her. She is tired, having flown some distance from her usual watering hole, but as she approaches, she slows, waiting to be impressed by the little male. He is small even for his age, owing to the lean times of his youth, and though they may be among the last viable mating pairs of their species in the entire world, she still waits for him to impress her with his mating display. In another world, she may have left, unimpressed by his dance and calls and never found a viable mate, or perhaps finding a mate, but without as good a nesting location as our little male, dooming their species. But here, in this world, the little male’s dance has done its job, and the little female coos back to him, letting him know that she approves.

A dozen similar stories play out in the Australian gateways, not just with our little male’s species, but with a few other hardy little survivors. And with their success the doom that came to non-Avian dinosaurs that seemed so total, has been forstalled. There will be difficult times ahead as calcium clorate vaporized by the impact plunges the planet into a climate catastrophe, but Life Finds a Way.

—-

Let’s introduce our first survivor. Though you already met him on the shore of an Antarctic Lake.The speculative genus Antarctolestes.

Weighing in at a mere .45kg and at just 60 centimeters long, Antarctolestes Terminus is an Antarctic relative of Rahonavis and Overoraptor. Like its relative in Madagascar, it was capable of powered flight, though again, like its relative it was an awkward flier with bat-like flight strokes. However, unlike Rahonavis, and much more like the duck-esque Halszkaraptor, Antarctolestes was a semi-aquatic near-shore animal.

It fed on plants, fish, and crustaceans like many modern diving ducks in addition to having more generalist foraging habits. This strategy was employed to help the non-migratory dinosaur survive the months of darkness during the Antarctic winter. Though nowhere near as cold as modern Antarctica, the lean times of the deep winter required this little animal to maintain this generalist lifestyle for survival.

Like the Euornithean survivors of the K-PG Impact, Antarctolestes did not have the arboreal niche bias of the Enantiornithean birds that would not survive the extinction event. Instead of roosting in trees, A. Terminus built its nests in abandoned mammal burrows, again a strategy to deal with the harsh Antarctic winters. With many members of A. Terminus having been fattened up in preparation for winter and held up inside their underground burrows at the time of the meteor impact in the Yucatan, they were prepared to deal with fire storms that overtook the world in the immediate aftermath of the strike. And while it did not have the beak that some accredit to helping the Euonitheans survive, its adaptations as a small generalist shore-side omnivore preserved the species. The little therapod’s teeth serrations were farther apart than those typical of strict carnivores making them similar to the Troodontid Byronosaurus. These wider serrations allowed the small animal to process plant matter and the seed-bearing cones of Antarctica’s decimated trees in the years with no sun, supplementing their diet of small fish and crustaceans that survived in Antarctica’s freshwater ecosystems.

Antarctolestese is the lone survivor of the non-Avian Therapods. Our little Male and female will be a wellspring from which new clades will emerge to conquer South America, Australia, and Antarctica. But they are not alone among the survivors of the non-avian dinosaurs. Let us venture ten decades after the impact to meet them.

It has been a hundred years since the world ended and one could be forgiven for thinking it hadn’t. There are no old-growth forests and gymnosperm trees have yet to fully recover, especially under the onslaught of acid rain, but amid the ashen husks of dead trees stand a few persistent survivors, and at their base, a menagerie of angiosperm flowering plants and ferns create thickets and brambles. It is not a silent forest either. The whistles and chirps of birds and insects fill the air

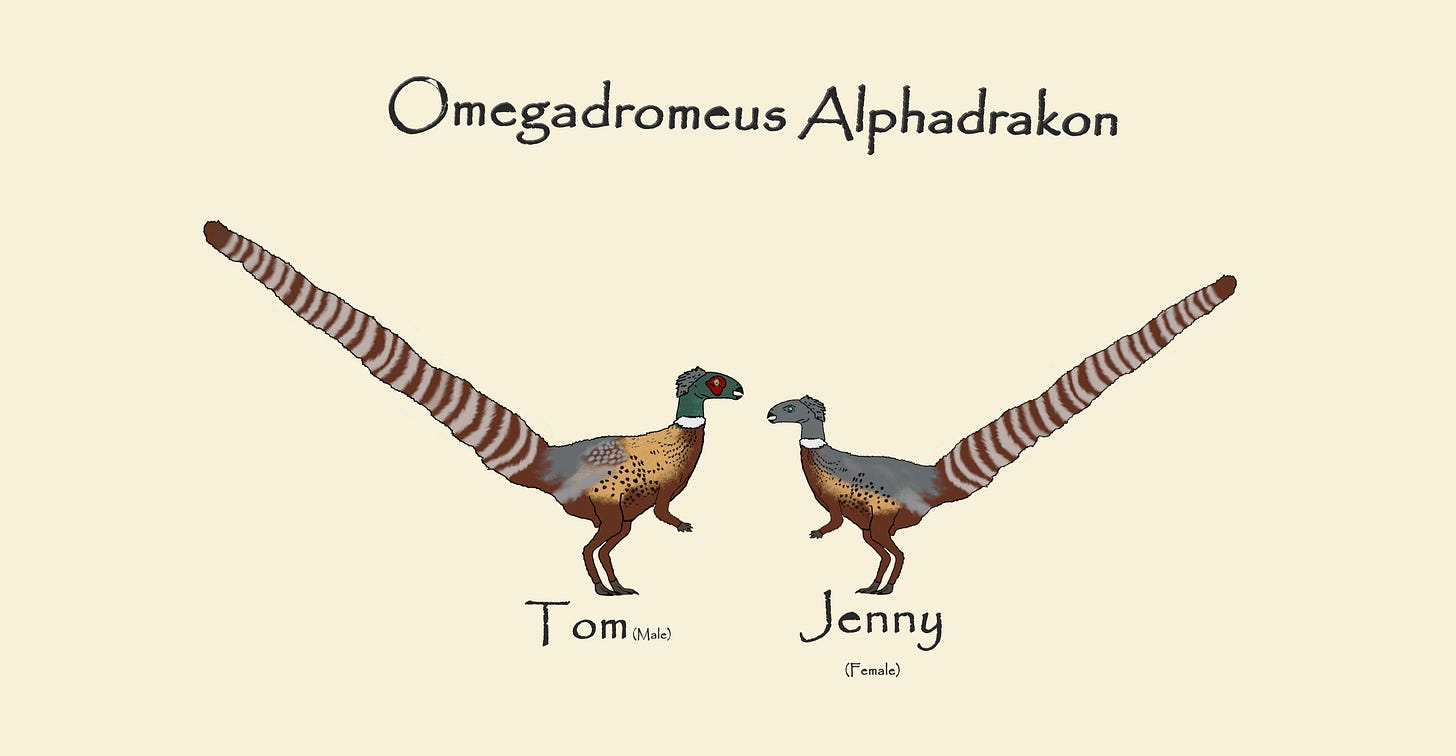

and on the forest floor small birds, reptiles, and mammals clamber through the leaf litter scrounging for food. This particular bird is not a member of Aves. It is an elasmarian that will one day be known by a species of hairless apes as Omegadromeus and this Jenny is a recent colonist of the area. In this western region of central Antarctica, no herbivores managed to survive the K-Pg strike and the impact winter that followed. Much like the Tullock Formation in North America, even small herbivores failed to survive the impact leaving only small detritivores to lay claim to the region. However, again like in the Tullock Formation small herbivores that survived the extinction event in distant refugium have begun to colonize the area as the ferns and angiosperms terraform it.

This female is one of the largest animals in the region and has lived much of her life without fear. The largest theropod, Antarcolestes could barely even threaten her as a hatchling, now that she is a 12-kilo adult, she is more than 10 times the weight of even the largest therapod or carnivorous mammal on the planet and more than capable of dealing with one of the little paravian predators. Even the shores of streams and lakes are completely safe to linger at as Crocodilians have yet to recolonize the region. On the macro level, semi-aquatic croc relatives and ancestors survived the K-Pg event handily, but in regions like Antarctica climate change prior to the K-Pg and the decade without summer that followed it led to localized extinctions that the region has not fully recovered from. With the last of the giant Temnospondyls who likely could have weathered the cooler climate having been driven to extinction 54 million years before the K-Pg event, the waters are without any dangerous ambush predators.

That security is what has driven her from her home further east into these lands. Where once the little elasmarians had their populations held in check by large predators and then scarcity caused by the meteor impact, now they experience scarcity caused by overpopulation.

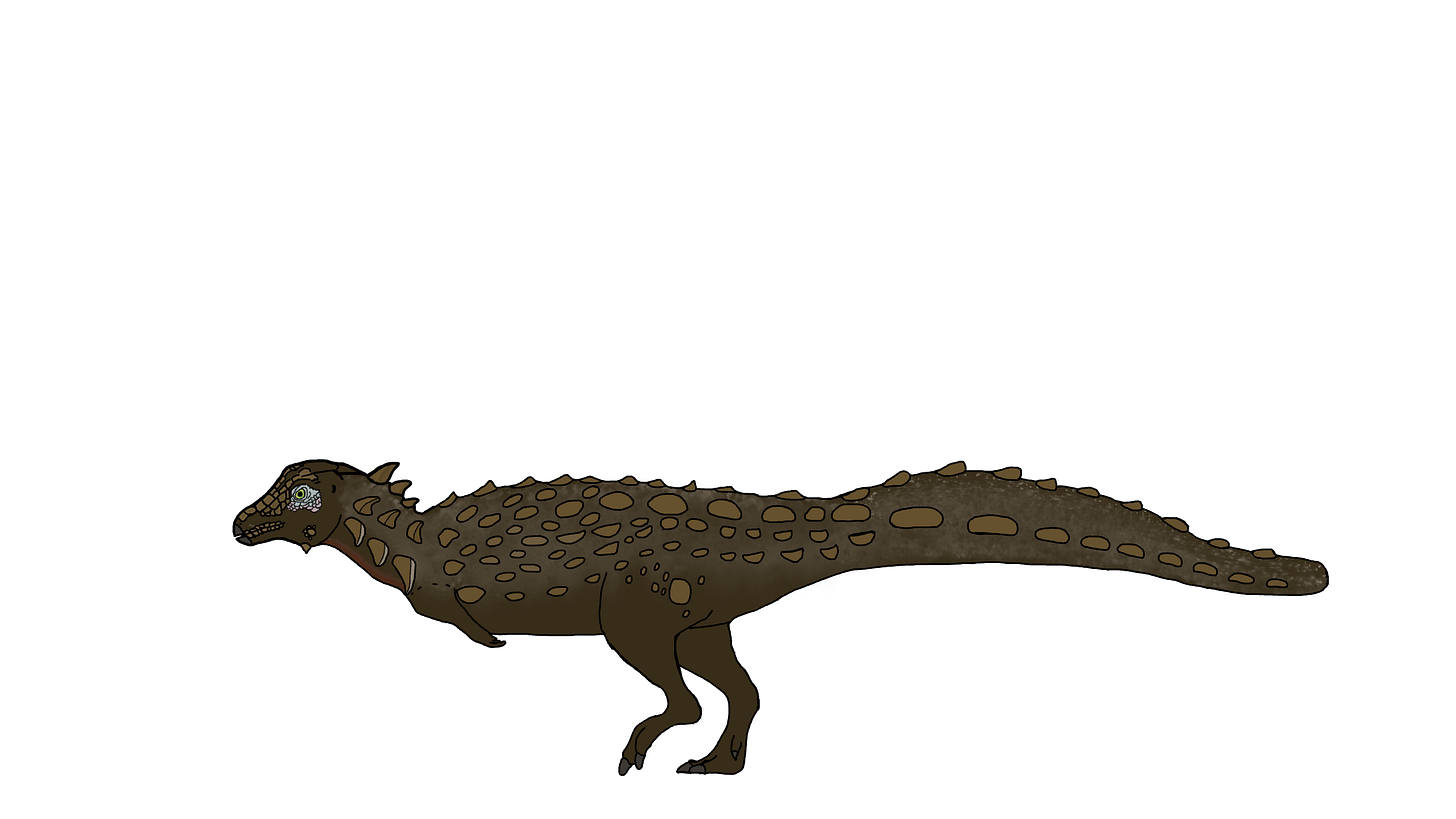

So now she ventures into the strange new land to make a home for herself, but she soon discovers that her kind are not only surviving non-avian dinosaurs to do so. Trundling through the underbrush toward her is one of the few other animals in Antarctica approaches her weight. It is a strange animal that walks like our Jenny but is covered more in scales and osteoderms than feathers and it looks a bit like someone smashed together a tuatara, a turtle, and an elasmarian. The strange creature pays the little female no mind as it searches the underbrush for fungi, seeds, and shoots. A hundred years prior, the strange little animal’s armor would have severed a secondary purpose to defend itself from attack by animals like Imperobator or adolescent Megaraptorans, but long after the larger theropods are dead and gone, they still see use in their original purpose, conflicts between males during the mating season. But our Jenny here doesn’t have to worry about such things.

The plant life here isn’t fully recovered, acid rain still harms the trees, and it will likely be a few thousand years before the last of the damage from the impact has completely vanished, but the world is already moving on.

Let’s look at the Little Elasmarian.

Omegadromeus alphadrakon or Last Runner First Dragon a name which references Revelation 22:13 as its presence before and after the K-Pg marked it as one of the last of the non-Avian dinosaurs of the Mesozoic and one of the first "dragons" of the Cenozoic. A relative of Trinisaura of the Snow Hill Island Formation further west, Omegadromeus has a significant number of similarities with its cousin and there are still arguments as to whether the genus is valid. Prior to the K-Pg, these little animals topped out at about 1.8 meters long (most of which is tail) and 13 kilos in weight making them about the same size as trinisaura but significantly smaller than the third Antarctic Elasmarian of the Maastrichtian, Morrosaurus which because of its size had a more extensive range than either of its smaller relatives. Like Trinisaura and other Elasmarians, Omegadromeus was built for speed. Its slim metatarsus and more developed caudal femoralis lent themselves to swift running through the Antarctic underbrush. However, unlike Tinisaura, Omegadromeus had a longer tail. Which despite hindering its ability to escape predators in some ways was a sexually selected trait similar to peacock feathers. This is in part, because, unlike Antarctolestes, Omegadromeus had more primitive plumulaceous feathers rather than the Pennaceous feathers of paravians which provide a broader surface to display from. The long banded tail along the bright green and red heads of males are strong indicators of animal health which ultimately led to them having a longer tail than their western Antarctic cousins.

The Lopez de Bertodano Formation of Seymore Island shows that the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction in Antarctica was as severe as lower latitude locations, however, we know from the colonization Tullock Formation by surviving herbivores that the post K-Pg landscape was not uniform. In their small refugium in Eastern Antarctica, Omegadromeus persisted through the worst of the extinction because of a combination of factors. The first being its slower growth rate and its reaching of sexual maturity long before skeletal maturity. With its less resource-intensive growth rate the animals were able to make do with less and with its early sexual maturity and rapid K-style reproduction strategy, it meant that despite high mortality rates suffered during the impact winter, the species maintained a robust enough population to not fall into an inbreeding depression.

Another significant factor in the species' survival was their semi-fossorial nature. Similar to Thescelosaurs the little elasmarians dug burrows underground to nest in during the prolonged Antarctic winters. This protected many of them from the worst of the global forest fires that spread after the impact. A third important factor is that despite predominantly being an herbivore, Omegadromeus was able to eat rotting trees to consume, fungi, insects, and crustaceans living within them much like larger ornithopods are known to have done. These factors, combined with a little bit of luck allowed for the persistence of Omegadromeus while its relatives went extinct.

Most of these factors also apply to the lone surviving thyreophoran, Eoaspisaurus, which in many ways resembles its Campanian relative Jakapil of South America. With 28 million years between Jakapil and Eoaspisaurus, there is a large ghost lineage between the two, however, this is a significantly more subdued gap than the nearly one hundred million-year gap in the fossil record between older basal thyreophorans like Scelidosaurus and Jakapil.

While it would be easy to write off Eospisaurus’ survival under an umbrella description of the surviving non-avian dinosaurs as all small being semi-fossorial generalists, to do so would minimize some of the unique elements that played a role in this small thyreophoran’s survival. Unlike the Jurassic Thyreophorans, Eosapisaurus had a much more efficient and derived masticatory system similar to its ancestor Jakapil, which had possibly evolved as a way to process tougher desert plants but was useful in the Antarctic climate to process tougher woody plants which animals like the long-toothed ankylosaur Antarctopelta would not have been able to exploit and which allowed it to subsist in part as a detritivore during the impact winter.

In addition to this efficient method of mastication, Eoaspisaurus also had unique caudal fat stores in its tail similar to what some lizards have and what some Carcharodontosaurs may have had. Like Jakapil’s superior mastication, these caudal fat stores may have evolved first as a feature for life in the desert but were repurposed to sustain the animals during periods of torpor in the Antarctic winter. These desert adaptations repurposed for Antarctic survival gave Eoaspisaurus the edge it needed to survive while others did not.

With food in abundance and no large predators, members of both species have begun to get larger and a little bit slower than their pre-K-Pg counterparts, nothing even statistically relevant yet, but as time goes on that will change. There are three loosely connected continents for them to expand across and diversify in and as the world continues to recover these little survivors will not remain little for long.

So now that we’ve introduced the three survivors, I’d like to discuss the fourth survivor who wasn’t. In his hour-long talk for the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology on mammal survival and the K-Pg extinction, Dr.Greg Wilson discussed how in the Tullock Formation, insectivores and detritivores appear to be the only survivors in that region of Montana after the K-Pg with herbivores recolonizing the region later. Because of this I strongly considered a theoretical Patagonykine Alvarezsaur as a second surviving Theropod. While the latest known South American Patagonykine is the 71-kilo Bonapartenykus, making it entirely too large to have been a plausible survivor, it was unlikely to have been the only Gondwanan Alvarezsaurid. With preservation bias likely being the answer to where the little Maastrichtian Patagonykines are. An animal about the size of Patagonykus or the more basal Alvarezsaurus seems like it could have been a plausible survivor, feeding on small insects that survived the extinction. However, I ultimately decided that their more specialist diets would have hindered their survival too much and though a small Alvarezsaurid may have survived the impact, even a generous amount of luck would not have preserved them through the scarcity of the impact winter.

So there you have it. The three surviving clades of non-Avian dinosaurs that we will be following as they spread out from Antarctica into South America, Australia, and eventually North America. Next video we will jump further forward into the Danian stage of the Paleocene to see how our little survivors and the mammals they live alongside have adapted to a world without giants

--

Do you have plans for a written version of the current iteration of Dragons of the Cenozoic?